ARTS, STYLE & ENTERTAINMENT

This is YOUR lifestyle gallery – of what is new and what is happening in the U.S. And the Black World, not excluding Africa. For this section if you have any news we should know about – let us know at: lifestyle@theafricantimes.com

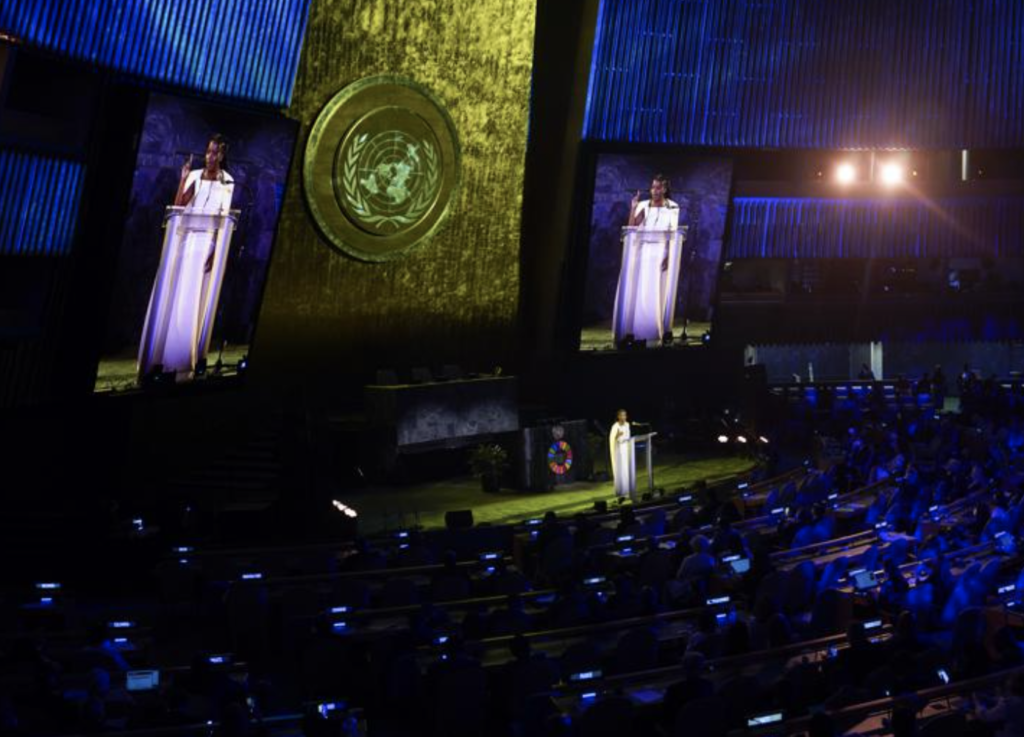

Courtesy/AP

When Amanda Gorman was invited to read a newly developed poem at the U.N. General Assembly recently, the young sensation took a deep look at how several societal issues — such as hunger and poverty — have impacted Earth’s preservation.

Just like her stirring inauguration poem last year, Gorman felt compelled to express the impact of unity through her poetic words on the opening day of the 77th session Monday in New York. The 24-year-old poet created “An Ode We Owe” in hopes of bringing all nations together to tackle various issues of disparity along with preserving the planet.

Gorman once again graced center stage in front of world leaders.

Her fame exploded after she recited her poem “The Hill We Climb” at President Joe Biden’s inauguration, which made her the youngest inaugural poet in U.S. history. Her poem quickly topped bestsellers lists and made her one of the most in-demand poets, putting her on other big stages like the Super Bowl and in an interview with Oprah Winfrey.

In an exclusive interview with The Associated Press (AP), Gorman talked about her hopes for the U.N. poem, her future presidency plans, resentment she’s gotten toward her commercial success and wanting to someday write a novel.

Remarks have been edited for clarity and brevity.

AP: What do you want listeners to take away from your poem?

GORMAN: What I hope people can garner from the poem is that while issues of hunger and poverty and illiteracy can feel Goliath and are so huge, it’s not necessarily that these issues are too large to be conquered. But they’re too large to be stepped away from.

AP: How important is having a young voice like yourself to speak at the General Assembly?

GORMAN: When I was writing this poem, I kept getting flashbacks of several years ago when I came to New York for the first time. I was 16 and I was coming as the United Nations delegate for the Commission on the Status of Women. That was the first time I’d really ever engaged the U.N. as a space in any way. I just remember not seeing people who looked as young as me. I also looked like I was 11 at the time. I started marinating on this idea of “I want to come back someday in the future. I don’t just want to be a delegate. I want to be a presenter.” I’m not here to speak on behalf of young people, but to speak alongside and with them.

AP: Why did you touch on Sustainable Development Goals in your poem?

GORMAN: I actually think that there’s swaths of the population which has yet to be engaged or kind of told or activated around the Sustainable Development Goals. So much of what I like to do in the poem is making sure that we raise awareness around these issues and show that these goals do exist.

AP: How have you managed the transition to being a high-level celebrity?

GORMAN: I’m still learning and growing so much. I think one of the things that changed so much for me was just privacy. All of a sudden I became someone — which I never really necessarily expected — who gets recognized on the street. If I go to a restaurant, even if I’m wearing a mask, people are very good at spotting my face and or my voice. I’m very grateful for that type of visibility, even though sometimes I do miss individual privacy because it means that I have a platform that I can use for good.

AP: How have people approached you while in public?

GORMAN: I had an experience (Saturday) night. I was eating at a restaurant and a woman just came up to me and started crying and saying how much my poetry meant to her. It’s flabbergasting to me. That’s not a rare occurrence in my life anymore. My friends started crying around me seeing this woman’s emotion. I had a great conversation with that woman before she moved on, and me having to take a moment, sit with the fact that there were so many people around the world who probably have this person’s same response that haven’t gotten to me. I want to do justice by them when I write. I want to honor them when I write. That’s a really hefty ask. But I also think it’s a deep seated privilege of mine. I think that’s the thing that I wrestle with and draw power from when I write.

AP: Has the fame changed your writing?

GORMAN: I think it hasn’t changed my writing in the sense that my voice and style is still the same because the roots of where I come from are still there. But I do think it makes me think more creatively and imaginatively about ways in which I can get those poems in the world.

AP: Is it much harder to write these days?

GORMAN: I think the main difficulty in writing poetry for me nowadays is, yes, that there’s a lot going on. But even if I’m able to carve out time and space to write, I think the biggest challenge that I can face sometimes is just my own self-sabotage in the sense that I feel so much pressure and so many eyes on me.

Amanda Gorman recites a poem during an event called at United Nations headquarters. (AP Photo/Seth Wenig)

AP: How do you keep out the distractions?

GORMAN: I’m like a 70-year-old in an 11-year-old body. I have muscles from that of pulling away from technology and pretending like it’s not there. Like it doesn’t exist. When I write, I tend to put all my devices on “Do Not Disturb.”

AP: Have you had to deal with any resentment from the poetry community, who sometimes don’t look kindly upon commercial success?

GORMAN: The only type of trolling that I experience is actually not from other poets. It’s from people who don’t write poetry. I hear those kind of like “What Amanda Gorman does isn’t that difficult. I don’t understand why she’s famous.” I have no ill will towards those people. I actually, in a sense, feel bad for them because more often than not, these are people who haven’t been exposed to a lot of poetry in their lives, who haven’t been either encouraged or challenged to write poetry in their lifetimes.

AP: What are your thoughts toward those skeptics?

GORMAN: I think the one thing I have to say to those people would be if you’re reading my work and you’re saying, “Amanda Gorman’s writing is so easy for me to do and I can do better.” Oh, my God. We need you. We need you to pick up a pen and write. That means you’re going to be the next great voice of literature. I would love for you to find a way to, for lack of a better term, dethrone me.

AP: Do you still plan to run for president someday?

GORMAN: Yes, that’s still the case. I obviously have a long way to go — not just in terms of years, but in terms of learning.

AP: Is there a timetable?

GORMAN: No, I’m just living and enriching my life with the understanding of “Wow, girl you are a weapon of cultural and poetic power. Here’s where you decide what to do with it.” Whether that follows a specific table that’s explicit for the presidency or whether it’s one that’s a bit more unorthodox and nontraditional than we’ve seen, I think remains to be seen.

Amanda Gorman recites a poem during an event called at United Nations headquarters. (AP Photo/Seth Wenig)

AP: Do you aspire to write something besides poetry?

GORMAN: I love poetry, but I love all forms of writing. When I was younger, I actually wanted to be a novel writer. But novels just take — for me — a longer amount of time than a single poem. That’s just how my brain and writing works. But I would love to get out some more prose, some more essay writing. You’ll definitely get more than just a verse for me.

AP: What kind of novels?

GORMAN: I really like to draw from what I consider to be my literary ancestors Zora Neale Hurston or Toni Morrison, who wrote this beautiful prose, which I think came out a culture of language that they drew from the African American community. I think about the titans of writing whose footsteps I would love to dance in.

___

Text of Amanda Gorman’s poem, “An Ode We Owe,” first read to the 77th U.N. General Assembly Sept. 2022 in New York:

How can I ask you to do good,

When we’ve barely withstood

Our greatest threats yet:

The depths of death, despair and disparity,

Atrocities across cities, towns & countries,

Lives lost, climactic costs.

Exhausted, angered, we are endangered,

Not because of our numbers,

But because of our numbness. We’re strangers

To one another’s perils and pain,

Unaware that the welfare of the public

And the planet share a name–

–Equality

Doesn’t mean being the exact same,

But enacting a vast aim:

The good of the world to its highest capability.

The wise believe that our people without power

Leaves our planet without possibility.

Therefore, though poverty is a poor existence,

Complicity is a poorer excuse.

We must go the distance,

Though this battle is hard and huge,

Though this fight we did not choose,

For preserving the earth isn’t a battle too large

To win, but a blessing too large to lose.

This is the most pressing truth:

That Our people have only one planet to call home

And our planet has only one people to call its own.

We can either divide and be conquered by the few,

Or we can decide to conquer the future,

And say that today a new dawn we wrote,

Say that as long as we have humanity,

We will forever have hope.

Together, we won’t just be the generation

That tries but the generation that triumphs;

Let us see a legacy

Where tomorrow is not driven

By the human condition,

But by our human conviction.

And while hope alone can’t save us now,

With it we can brave the now,

Because our hardest change hinges

On our darkest challenges.

Thus may our crisis be our cry, our crossroad,

The oldest ode we owe each other.

We chime it, for the climate,

For our communities.

We shall respect and protect

Every part of this planet,

Hand it to every heart on this earth,

Until no one’s worth is rendered

By the race, gender, class, or identity

They were born. This morn let it be sworn

That we are one one human kin,

Grounded not just by the griefs

We bear, but by the good we begin.

To anyone out there:

I only ask that you care before it’s too late,

That you live aware and awake,

That you lead with love in hours of hate.

I challenge you to heed this call,

I dare you to shape our fate.

Above all, I dare you to do good

So that the world might be great

Jacob Lawrence (1917-2000) was the first African American artist included in the permanent collection of MoMA The Museum of Modern Art, where he had a solo exhibition in 1944. He spent his formative years in Harlem, which was at the center of African-American cultural and intellectual revival. Lawrence started to integrate studies of history with his own experience, with depictions of civil rights confrontations and scenes of daily life.

Your comments, ideas, and thoughts matter.

Drop us a line: