ARTS, STYLE & ENTERTAINMENT

This is YOUR lifestyle gallery – of what is new and what is happening in the U.S. And the Black World, not excluding Africa. For this section if you have any news we should know about – let us know at: [email protected]

By Tinashe Mushakavanhu

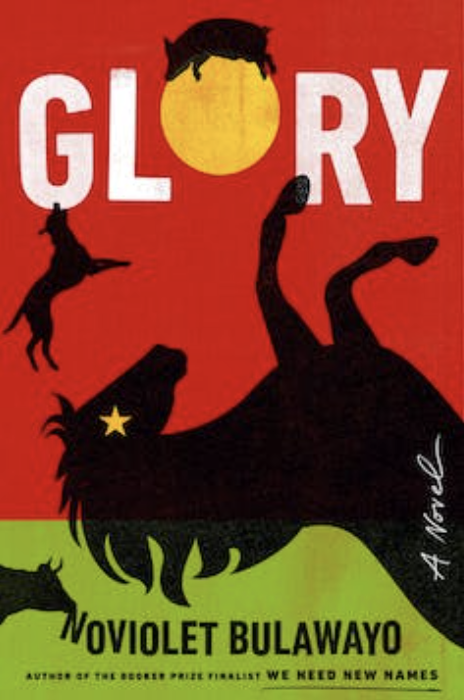

In Zimbabwean author NoViolet Bulawayo’s new novel Glory – longlisted for the Booker Prize 2022 – animals take on human characteristics. Through this she explores what happens when an authoritarian regime implodes, using characters who are horses, pigs, dogs, cows, cats, chickens, crocodiles, birds and butterflies.

Bulawayo’s celebrated first novel, We Need New Names, was a coming-of-age story about the escapades of a Zimbabwean girl named Darling who ends up living in America. Its hallmarks are accentuated in this new work: the troubled real world of class struggles, psychological dualities, colonial and postcolonial histories, war and the dog-eat-dog politics of contemporary Africa.

Glory is set in a kingdom called Jidada, which could be Robert Mugabe’s Zimbabwe, Idi Amin’s Uganda, Hastings Banda’s Malawi, Mobutu Sese Seko’s Zaire, Emmerson Mnangagwa’s Zimbabwe or any other authoritarian regime in Africa, for there are many. The tropes Bulawayo makes fun of are so recognizable and familiar.

Perhaps as memorable as the names in her first novel (Bastard, Godknows) are those of these animal characters (Comrade Nevermiss Nzinga, General Judas Goodness Reza). There is also a Father of the Nation, Sisters of the Disappeared and Defenders of the Revolution, Seat of Power and the Chosen. And there is the Soldiers of Christ Prophetic Church of Churches.

In fact, there is something almost playful about this book. When politics becomes a farce, it only requires a virtuoso like Bulawayo to marshal the faux pas into a memorable fictional narrative.

The novel fictionalizes the real politics of Zimbabwe, from the removal of Mugabe to the rise to power of his former vice-president, Mnangagwa, in 2017 and the years since, during which Zimbabwe’s economy has suffered and the political promises of the “second republic” have gone unfulfilled.

Chatto & Windus/Penguin Books.

Humour as resistance

In an interview in the immediate aftermath of the Zimbabwe coup d’état in 2017, Bulawayo talked about attempting to write about the fall of Mugabe in nonfiction but abandoning that effort. She found the novel to be a better form for political satire.

Bulawayo’s writing is distinctive. There is a lyricism to her prose, a poetics of language that mesmerizes and surprises. This gives her fiction an applied, intense focus.

Glory has a lively rhetorical idiom; it is full of color and vigor. As one reviewer wrote: “Bulawayo is really out-Orwelling Orwell.” Both authors reference the disarray and traumatic conditions of the world in a distinct and powerful way.

e between 1983 and 1987 when more than 20,000 people were massacred in Matebeleland.

The challenge for Bulawayo, or any writer for that matter, was how to write about a coup still in progress that was described as a-coup-not-a-coup. How could one write about the events that started when Mugabe was overthrown with the promise of new Zimbabwe that is yet to come?

Greatest Leader of Jidada, Enemy of Corruption, Opener for Business, the Inventor of the Scarf of the Nation, the Survivor of All Assassination Attempts…”

It is a particular challenge to write about regimes that enforce everything with violence. And yet Bulawayo’s vibrant satire succeeds in telling a political parable that also reflects the times.

Chatto & Windus/Penguin Books

Your comments, ideas, and thoughts matter.

Drop us a line: